mary leonard

¿qué hacer con el dolor?

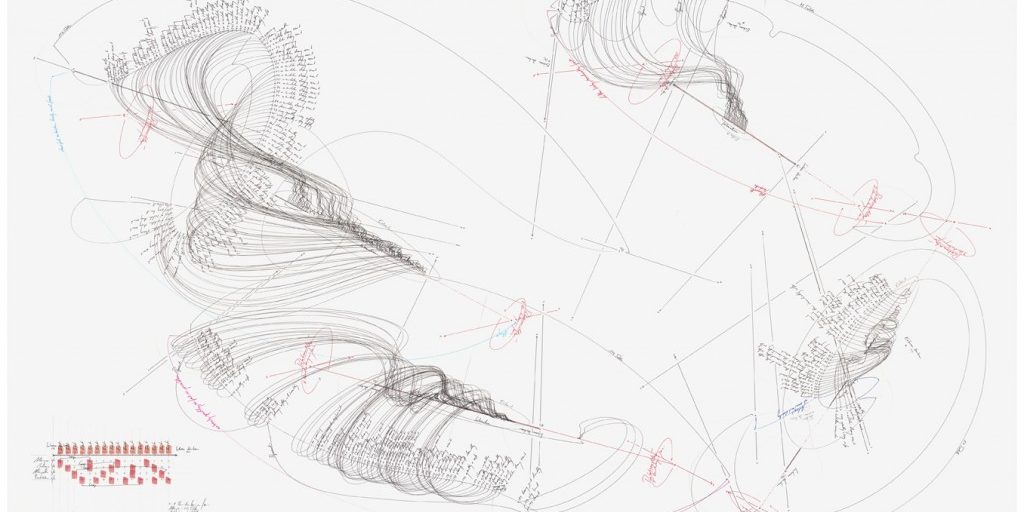

the uses of silence, images, wordsTinta regada

1 de agosto de 2024

I think of how it is possible to respond to collective and personal traumas caused by, among other things, the repeated shocks to the system of economic and energetic crises, of natural disasters, of violence, of separation, of loss, and of death. How is it possible to look at pain? What do we say? What do we not say?

silence

In 1921, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” (“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen.”) Sometimes language is not adequate when there are no words, or the right words cannot be found. Sometimes silence is preferable because we cannot speak of what we do not have words for, or of what we cannot conceive.

W. G. Sebald writes about this in The Natural History of Destruction. Why is it he asks that so little has been written of the firebombing of 131 German cities by Allied Forces at the end of World War II, an event that completely annihilated many of these cities, and made seven and a half million homeless? It was because the instantaneous and utter destruction of everything they knew left the survivors in a state of dumb shock from which they could not recover. Kurt Vonnegut, at the time an imprisoned American soldier in Dresden, emerged onto the lunar landscape of what had been one of the most beautiful cities in Europe from an underground meat locker where he had taken refuge during the bombing. “The city was gone.” he recalled, “They burnt the whole damned town down.” It took Vonnegut many years to find the right words to tell the story. He wrote obsessively about it for decades, but threw most of this writing out, until finally publishing Slaughterhouse-Five in 1969.

The Dominican writer Hilma Contreras understood that silence contains and preserves what words dissipate, and knew how to conserve the unsayable. During the claustrophobic years of the Trujillo era, she penned short stories suffused with dread in which the austerity of the language contrasts with the tension and anxiety produced when dangerous desires are repressed or resisted, or threatening natural disasters move ever closer. She sought solitude, silence. Her writing exuded more than it said:

silencio antes de nacer

silencio después de morir

vivir anhelante entre dos silenciosimages

Images capture sensation differently than words do. In Sebald’s novel Austerlitz, set in the years after World War II, the main character has been adopted and raised in the sober, largely silent home of a Calvinist minister and his wife, who never tell him where he came from or who his original family was. As an adult he traverses Europe taking photographs as if to try to grasp through them the traces in his subconscious of a personal history originating in another country and in another language that he has not been given the words to understand. Towards the beginning of the book, there are two photographs of the eyes of Ludwig Wittgenstein, the first of the young Wittgenstein who wrote about choosing silence, the second of the older man who had come to understand the power of visual images to capture what could not be named. “Don’t think, but look!”, wrote the older Wittgenstein in The Philosophical Investigations. The eyes capture, he knew, but perception is molded into something different when put into words: “You learn…the concept ‘pain’ when you learn…language.”

Because “pain” is a word understood by others it makes it possible to describe what otherwise exists only as sensation. But “pain” may not accurately describe the exact sensation that another feels. We cannot assume that we completely know what others are experiencing. It is perhaps for this reason that some, like Contreras, defend their inner lives by choosing silence, instead of speaking about sensations and feelings in a way that allows them to be fixed in language and lays them open for public view.

words

Others do not lack or fear words. They do not seem to fear naming sensations. Perhaps they, like Freud, believe in the talking cure, in the therapeutic value of language to change sensations, and choose that route. Or perhaps, like Susan Sontag, they trust in their own ability to use language to change the perceptions of others in order to gain agency and control over their own experience of pain and illness, as Sontag did in Illness as Metaphor. In this book, written in 1978, Sontag, who had been diagnosed with cancer, rejected what she called the “lurid metaphors” often used to describe the disease as shameful, horrific, and obscene, and sought to strip it of the associations that portrayed the sick person as “robbed of all capacities of self-transcendence, humiliated by fear and agony.” “Illness is not a metaphor,” she argued, “and…the most truthful way of regarding illness—and the healthiest way of being ill —is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking.”

what to do with pain

¿qué hacer con el dolor?

Today, in the Caribbean and Central America, awash in and connected by the media we all swim in, what forms are being used to process the pain of loss?

This section examines three examples of how this has been done recently, and is now being done: the use of words and images in Facebook eulogies; the way postmemory films in Central America overcome silence; and the sensory world of the films of Glorimar Marrero, in which what takes on importance when characters suffer in silence are acts of empathetic accompaniment.

facebook eulogies

Waves of deaths and long long Facebook eulogies. So many posts in which people write at length about their memories of a person, of the qualities that distinguished them from others, of the particularities of their relationship, of appreciation, of affection. There are also the photographs. Below them are the comments. Each eulogy is long and took a lot of time to write. They are different from each other. They feel spontaneous. It seems no one is afraid to speak. They mass together, a torrent of words and images that memorializes as a communal act, that washes over the internet, and then fades away. I see this only in Puerto Rico. Is it a Puerto Rican genre?

postmemory

Central American cinema came of age in the wake of the civil wars that harrowed the region in the late twentieth century. Because of this, many filmmakers are the sons and daughters of those who suffered during the violence of that time, of people who were tortured or killed. But the older generation generally maintains its silence, and the younger generation hesitates to ask hard questions. However, some of the films of this generation are asking these questions.

In 2012, a volume of essays titled The Generation of Postmemory was published that examined writing and visual culture produced after the Holocaust by the generation of artists born after the war. Though they did not directly experience what their parents’ generation did, writers and artists like Sebald felt the effects of trauma passed down through families, through behaviors, through images and stories that still reverberated throughout the culture.

In her film Los ofendidos (2016), Nicaraguan-Salvadoran filmmaker Marcela Zamora, after learning that her father had been tortured for 33 days during the civil war which took place in the 1980s, records her conversations with him and others about their experiences in a film which is about the act of speaking and relating as much as it is about the information provided. At one point, Zamora is heard crying off camera after listening to an account of torture. The interviewee framed in the shot smiles sadly, “Lo siento.” At another, the filmmakers joke around. In varied exchanges, the rapport Zamora has with those she interviews, tortured and torturers, shows us an insider’s view of a country engaging with the aftermath of conflict. This is not what some have criticized as the “poverty porn” of films that seek to elicit an emotional response to dramatic scenes of poverty and violence without resolution, seen from a comfortable distance.

accompaniment

La pecera is a film about pain that has resonated enormously with audiences in Puerto Rico. This film, like Glorimar Marrero’s other films, most of which were made in the aftermath of the death of her mother from cancer in 2013, are about how to respond to pain and suffering. They contain little dialogue and what words there are are incidental to what is really happening, which occurs on a sensory level.

In the wordless Amarillo, a 2014 film Glorimar wrote, a man in a wheelchair makes his way anxiously through a crowded hospital corridor to the room of a man who lies unconscious in a dark and dusty room and throws open the curtains to let in the yellow light of day. Nothing else can be done for the sufferer. In the world of this film, almost everyone is overwhelmed by their own problems. The resources that are needed are not there. No help is on the way.

In Todavia (2016), a woman accompanies a friend who is in a profound state of depression after having had a mastectomy. The woman first offers her friend company. She combs her hair, applies make up, and tries to fit her with a prosthetic breast, but this is rejected. She then tries paying a man to provide her friend with sexual services. When this does not work either, she finally takes off her clothes and presses her body against the woman as she lies in bed anxiety-ridden, embracing her, skin on skin. Glorimar has talked about the importance of skin: “The power of skin is greater than we know or imagine. I believe in the power of touch and its effects on the nervous system.”

The short film Biopsia (2016) is also about breast cancer, this time on the island of Vieques, where the disease is rampant. As is usual in Glorimar’s films, it begins in media res, without an explanation of where we are. It is early morning as a van full of women makes its way to the island port. The women board a ferry that takes them on the long journey to the main island, then go on to the capital, and then wait more time in a doctor’s office, before they finally receive the biopsies they have come for. The film feels like a documentary. It is slow, emphasizing the length and difficulty of the journey, and ends painfully with the insertion of the biopsy needle.

La pecera too tells a story of cancer, of the physical and emotional suffering of Noelia, a woman who returns to Vieques after choosing not to continue the treatments that would keep her alive. It is a film that provokes discomfort, discomfort with sickness, with intimacy, with the inevitability of death. Some critics react against what they see as the selfishness of a woman who chooses to die without regard for what others close to her feel or want. Even Isel Rodriguez, the actor who plays Noelia, at first found the character self-centered and unlikeable. We are not used to seeing characters like this in films without being able to share their thoughts and feelings. But, in this film, it is the precisely the right to privacy, the right of sick and dying people to make their own decisions about their bodies and their lives without having to explain or justify them to others, and by extension the right of Vieques and of Puerto Rico to self-determination, that is the central idea. Noelia maintains her distance, her privacy, her autonomy. She does not let us in. But at the same time she suffers, is sensual in that suffering, and seeks solace in her own body. In looking for the character, Isel imagined her as a creature very much of her body, as sensorial and sexual despite her colostomy. This we do see, and it provokes discomfort because of the sensuality of a sick body that is displayed much more than we are used to seeing in films. But it is also this that provokes thought. As one reviewer in Puerto Rico wrote, “it made me feel uncomfortable, and I don’t mean in a bad way.” (“El largometraje me hizo sentir incómoda y no lo digo de mala manera.”)

Like Glorimar’s other films, La pecera is about pain stored in the body that is not spoken about. (What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.) But this pain is seen and felt by others and these films are about more than just suffering. They are also about what can be done in the face of it, even if that is only the act of accompanying the person who suffers with empathy and without judgement.