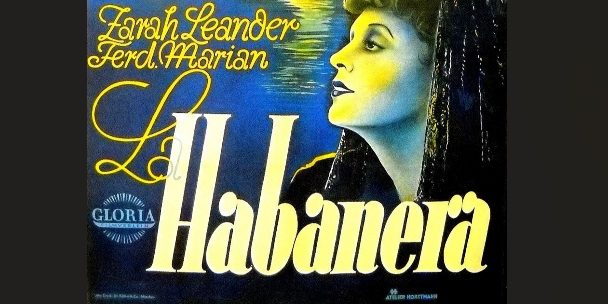

Jason Weiss

La Habanera

Tinta regada

1 de enero de 2024

The cascading ironies of a film production, its principal talents, its moment in time, and the surrounding circumstances, could not be more pronounced than in Detlef Sierck’s musical melodrama La Habanera (1937). A German film with a Spanish title, it traded in the exotic only to serve as a hackneyed warning. The German-born director, who emigrated before the film’s release at the end of the year, was soon to be known when he reached Hollywood as Douglas Sirk. Of Danish parents and married to a Jewish woman, he made the film for UFA, then under Nazi control, shooting partly at the company’s studio in Potsdam-Babelsberg; it was not his own project. The story had ostensibly nothing to do with Germans but rather a dark-haired Swedish woman who happily goes astray in Puerto Rico. Never mind that the habanera music she finds so enticing suggests a different island in the same sea and of the same language, a distinction of no importance since everyone’s speaking and singing in German. What matters, in the end, at least for the National Socialists, is that the remorseful Astrée, ten years wiser, returns to her homeland with her very blond son. Conveniently, she is released from her domineering though once gallant husband, Don Pedro, when he is struck down by the dreaded “Puerto Rico fever.” Driving the point home, one of her own countrymen rescues her, Dr. Sven Nagel, an old beau who has traveled to the pestilential paradise to find a cure. Which he does, in no time flat; if it weren’t that the jealous Don Pedro has it destroyed before they get any further.

For a country bent on a sick sense of nationhood at the time, boasting a fictive purity that would be laughable were it not so deadly, La Habanera was a popular entertainment with a purpose; little wonder that the writer became a member of the party. And yet, the whole enterprise was riddled with cultural borrowings and sleights of hand, to such an extent that the propaganda machine should have collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. If the island didn’t matter, the sea didn’t either, given that the exterior scenes were shot more easily in Tenerife, the Canary Islands, off the coast of North Africa. Which explains how the décor, the dress (except for the shepherd boy in a loincloth), the movements seem decidedly Spanish rather than Caribbean. Authenticity may have been irrelevant in the crafting of a message, but even the lead actors couldn’t manage to be good Germans. Ferdinand Marian (born Haschkowetz) was Austrian—close enough, considering—and the same physical aspect that enabled him to fit the part of Don Pedro, the generic Latin lover, gained him the title role a few years later in the viciously anti-Semitic film Jud Süss (Suss the Jew). In effect, he never lived it down, dying a year after the war either from drunk driving or suicide on the way to picking up his denazification papers. Coerced by Goebbels to take the part, his personal life suggested quite a different character: his first wife was Jewish, with whom he had a daughter, and his second wife had also been married to a Jew, whom they hid in their home.

Swedish singer and actress Zarah Leander, by contrast, lasted until the early 1980s, ever a controversial figure. Her greatest success was in Germany in the ‘30s and ‘40s, and in 1936 she signed on as a contract player with UFA where she made ten films; even so, two years later she recorded the Yiddish chestnut “Bei Mir Bistu Shein.” Color her confused. Astrée would seem a role tailor-made for her, the German-speaking Swede, as both the actress and her fictional counterpart carefully steered clear of local politics. Her stardom may have protected her for a while, but when her Berlin home was bombed in an air raid in 1943, she chose to return to Sweden. For the rest of her life, she insisted she had had no sympathy for the Nazis and was simply an entertainer. That may well have been: a career untouched by an agenda, untroubled by a moral center. But long after she was gone, claims arose that she had actually been a Soviet agent and was also a member of the Swedish Communist Party.

In its story, the film reinforced a principle that one should find strength and salvation in one’s own kind. But real life was too messy for such delusions. Sirk knew that as well as anyone. His first wife, a decade earlier, subsequently joined the Nazi party and was able to bar him from seeing their son because Sirk’s second wife was Jewish; the son, meanwhile, became a leading child actor in Nazi-era cinema, but eventually became a soldier and died at the Eastern Front, still a teenager. Likewise, the little blond boy who played Astrée and Don Pedro’s son Juan, in his only film role, was drafted before the end of the war and killed at seventeen fighting for the fatherland.