Michael Huffmaster

William Carlos Williams and Bibliotherapy

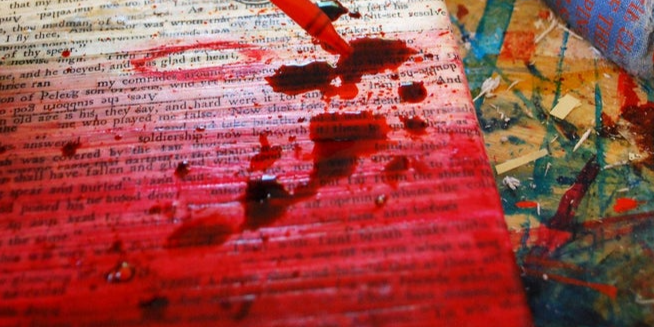

Tinta regada

1 de octubre de 2024

As a scholar of German (which is to say, not English or American) literature, I have what I would call an average educated North American’s familiarity with the poetry of William Carlos Williams. That is to say, I know the two poems “The Red Wheelbarrow” and “This Is Just to Say.” I have encountered both on a number of occasions in various contexts—most academic, but some private—and I find both brilliant, obviously, for all the reasons they have been appreciated by countless readers over the decades and continue to be to this day.

When the Biennial Conference of the William Carlos Williams Society was held in Mayagüez in February, the presentation titled “Medicinal Poetry: Words, Places, Code-Switching, and Healing in William Carlos Williams’s Language” by my colleague and friend Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera sounded especially intriguing to me. In July 2020, as the pandemic was in full swing, I learned from a series of broadcasts on the Austrian public radio station Ö1 of the field of bibliotherapy and was fascinated. I remember a conversation with a good friend in graduate school as we were both nearing the completion of our degrees about the possibility, if the academic job market didn’t pan out, of working as something like a life coach, but using literature as the coaching material. Neither of us had ever heard of such a profession. Ultimately, both of us were among the fortunate ones who landed academic positions, so we never had to pursue a “plan B.” But learning that it’s actually a thing, that there is such a profession, was thrilling. Since then, I have read several key texts in bibliotherapy and have been working toward training and certification. I believe it will enrich my teaching practice as well as my research agenda.

In one of the core texts of the field, Biblio/Poetry Therapy—The Interactive Process: A Handbook (2012), authors Arleen McCarty Hynes and Mary Hynes-Berry articulate the goals of bibliotherapy as fourfold: an improved capacity to respond, increased self-understanding, increased awareness of interpersonal relationships, and an improved reality orientation. These goals align with my personal and professional convictions about why literature is a cornerstone of liberal education. We tell stories. This is a universal practice, documented in all known cultures past and present. And we do so not just for entertainment—though that is crucial—but rather first and foremost for education. And education, as the German term Bildung connotes, is about formation of the self, of the person, which is the primary purpose stories serve in education. As Toni Morrison observes in her introductory remarks to her Nobel Lecture, “One of the principal ways in which we acquire, hold, and digest information is via narrative.” This is true, by the way, for all fields of knowledge. Narrative is not a literary genre: it is a fundamental and pervasive structure of human cognition. The words narrative and know derive from the same Indo-European root, gnō.

In academia, since the rise in the 1980s and eventual dominance of new historicism, works of art have been treated primarily as historical documents. I recall a conversation with a renowned film scholar, someone I deeply respect, who referred to an artwork’s “aesthetic surplus value,” as though its status as art were something peripheral but not essential to its nature. That is in fact the foundational theoretical premise of new historicism. I also recall a remark by a former colleague (not someone I respect), who commented, “We have to get them [that is, our students] to stop talking about their feelings,” as though in utter ignorance, willful or no, of the meaning of the word aesthetic. Everyone knows what an anaesthetic is; the word means “without feeling.” And aesthetic, from a late eighteenth-century German coinage, derives ultimately from a Greek word meaning “to feel.” To me, one of the most appealing aspects of bibliotherapy is that the “feeling-response,” as Hynes and Hynes-Berry call it, is central. Furthermore, the phases of the bibliotherapeutic process the authors describe—recognition, examination, juxtaposition, and self-application—strike me as an ideal template for any class session devoted to a work of literature.

From the overview of bibliotherapy I have acquired so far, William Carlos Williams is not a poet I have seen mentioned in the literature; I have never encountered a description of a bibliotherapy session using a poem of his, for example. That is why the title of Jeffrey Herlihy’s talk, “Medicinal Poetry: Words, Places, Code-Switching, and Healing in William Carlos Williams’s Language,” intrigued me. It was especially interesting to learn that Williams was a medical doctor by profession and that he used his prescription pad, always at hand, to jot down drafts of poems when they occurred to him—a practice that, given the spatial constraints, could help account for his innovative, characteristic form. I wondered if Williams, as a doctor, ever reflected explicitly in his diaries or private correspondence on the therapeutic potential of poetry, whether reading or writing it. I have not been able to ascertain the answer to that question, but it doesn’t matter ultimately.

My curiosity was piqued, so I got out my Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry (second edition, 1988) and reread through all the Williams poems included (except for the extended, twenty-page excerpt from Paterson), considering each through the lens of bibliotherapy, whether it would be appropriate for the approach. “The Red Wheelbarrow” struck me as imminently appropriate, as a concrete representation of the therapeutic experience of being intensely present and noticing, dropping all the mind-stuff about past and future and “getting real,” as it were: an ever-helpful reminder for everyone, be it in a therapeutic context or in everyday life. Elaborating on the bibliotherapeutic goal of improving the capacity to respond, Hynes and Hynes-Berry write, “Where beauty is perceived, an integration of the self takes place…. By responding to the beauty of a finely crafted poem, story, or play…or reflecting on an image that reveals the small beauties of the everyday world, the participant experiences a spontaneous pleasure” (17-18). “The Red Wheelbarrow” seems to me an ideal affordance to prompt precisely such a therapeutic response, as do a few more of Williams’s poems in my Norton Anthology, namely, “Queen-Ann’s-Lace,” “The Great Figure,” and “Flowers by the Sea.”

And I cannot help but think that Hynes and Hynes-Berry had “This Is Just to Say” in mind (along with a couple other poems whose allusions elude me) when they composed the following, expanding on their comments cited above about the value of responding to beauty: “It may seem a simple thing to foster the capacity to enjoy life, to be spontaneous and uninhibited enough to delight in the wonder of a snowflake, the taste of a cold plumb, the warmth of a room after the bracing cold of the outdoors. But for many, such simple healthy responses are too rare…. Recognition of the simple delights of the world around us can sharpen our awareness of the deeper wonders of trust, friendship, love, and appreciation” (18). “This Is Just to Say” struck me initially as appropriate for couples counseling, but on further consideration, it seems well-suited as an affordance to examine a range of interpersonal issues in a variety of contexts, for example, among roommates or coworkers.

“The Widow’s Lament in Springtime” (which my Norton Anthology informs me in a footnote was a tribute to the poet’s mother) struck me immediately as ideally suited to grief counseling. It reminded me exactly of how my mother could no longer find joy or pleasure in things she previously had after my father died. But then I had reservations about its appropriateness: perhaps it is too direct? Discussing criteria for choosing bibliotherapeutic materials, Hynes and Hynes-Berry stress that “the degree to which a work is positive and offers hope” (56; emphasis original) is a key factor. A work with a negative tone, they caution, could prompt feelings such as hopelessness that thwart the aims of bibliotherapy, “namely, to affirm the strengths of the participants, to improve their self-esteem, and/or to help them deal more creatively with their lives, particularly with realities they cannot change” (57). As an example, they mention Edwin Arlington Robinson’s well-known poem, “Richard Cory,” which concludes with the wealthy, popular, and by all appearances happy and successful title figure going home “one calm summer night” to “put a bullet through his head.” “There is nothing healthy about the message,” they state. The “poem offers neither any resolution nor any hint of how to cope successfully with” negative emotions such as “anger, envy, despair, or suicidal impulses” (57). The same could be said of “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime,” which ends with the lines: “I feel that I would like / to go there / and fall into those flowers / and sink into the marsh near them.”

In May, a friend died, whom I’ll call José out of respect for the family’s privacy. He was the patriarch of a local family that befriended me not long after I moved to Puerto Rico. They invited me to holiday celebrations, and they gave me shelter during and after Hurricane Maria. I went to the family home the day after José’s passing and sat a while with the family matriarch, whom I’ll call Rosa, consoling her as best I could and sharing memories of José. That day I brought three mesotrones from El Meson, remembering how grateful my mother and I were for all the food neighbors and friends and family brought us after my father died, because the last thing you want to do is cook or prepare food, but you have to eat, right? Whenever I visit, I always bring small tokens of my enduring gratitude for their hospitality and generosity, typically some local fruit (the guineitos were José’s favorite), chocolate for Rosa, and something else, flowers or what have you. (At Christmas, I bring a pernil.) But I felt, after José’s passing, I wanted to bring Rosa something more intangible, more meaningful. After my reencounter with Williams’s poetry, I knew I wanted to share with her his poem “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime,” despite the reservations. I remember my mother remarking how much she valued widowers’ group counseling (when she finally decided to go after a few months of resistance to the idea), simply because she could talk with other people who were going through the same thing she was. Similarly, although “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime” does not offer any suggestion of how to cope with grief, it could serve simply to prompt recognition of shared experience, in this case transcending space and time, and perhaps be therapeutic or emotionally beneficial that way.

I composed a one-page document with “The Red Wheelbarrow,” “This Is Just to Say,” and “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime,” and in July, I went to the family home with a printout. After the usual tokens—a pineapple, chocolate, flowers—I showed Rosa the printout and explained that I’d brought some poems I wanted to share, if that would be okay with her. She immediately agreed and invited me out to the patio, where we sat a good half hour or more. She mentioned at the outset, as though in affirmation of her enthusiasm for my gesture, that her mother wrote poems and recited them and that her brother also wrote love poems to a local girl. I explained the backstory and my motivation for wanting to share these poems—the Williams Society conference in February, that the poet’s mother was from Mayagüez, learning the poet was a doctor, my belief in the healing power of poetry. I also felt it important to convey Williams’s canonical status, so I mentioned that the first two poems are among the most anthologized in English literature, and I ventured that everyone who has ever finished high school in the United States probably knows either one or both of them.

I read each poem out loud while Rosa followed along on the printout. After “The Red Wheelbarrow,” she remarked something to the effect of “Yes, so true.” I spoke a bit about what I especially appreciate about the poem: its simplicity, the iconicity (the way each stanza visually represents a wheelbarrow on the page), its haikulike quality as a snapshot of a moment, and the therapeutic value it intimates (“so much depends”) of simply being present and noticing. After “This Is Just to Say,” she again remarked, “So true,” and she related a story about how she once baked a lemon pie for a friend (which I inferred she put in the refrigerator), but by the next day it was all gone. Her anecdote confirmed my sense that the poem could be appropriate for a wider range of contexts beyond couples counseling. Reading “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime,” I choked up a bit at two or three spots—recalling my own mother’s grief and empathizing with hers—but steadied through. Again she commented, “So true.” So despite the poem not offering any solution, I feel my hunch was validated that reading it might be beneficial as a moment of shared experience. We talked, in the spirit of the poem, about the flamboyán trees in their yard, which had been in bloom over the previous weeks but were all green now. I spoke about how the first year is especially hard because every anniversary, every birthday, every holiday is marked by absence. (José’s birthday coincided with Father’s Day this year.) But I got a sense of Rosa’s emotional and mental strength as she spoke about her deep faith in God and all she has to be grateful for. She mentioned having her children nearby, because she knows other widows whose children are in the United States. And she mentioned having her two youngest grandchildren at home, who keep her busy, demanding time and effort, of course, but who also thereby help keep her present, focused on the moment, as children are. When I signaled I was ready to leave, she thanked me again for bringing the poems. I thanked her for the opportunity to share them.

In conclusion, I would also like to thank the William Carlos Williams Society for holding their biennial conference in Mayagüez this year and my friend Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera for his talk. I am grateful for the entire experience it inspired: my rediscovery of Williams through the lens of bibliotherapy, and from that, though the occasion was a sad one, the opportunity to share the healing power of poetry. Gracias.