Jason Weiss

Potocki

Tinta regada

1 de agosto de 2024

From the start of his “Mémoire sur l’ambassade en Chine” (1806), about a failed Russian delegation he was part of that never got past Mongolia, Jan Potocki makes it clear that Western arrogance was to blame most of all. Or at least in the persons of the ambassador and his first secretary. “Far from wanting to know the character of the Chinese,” he writes, “they only seemed to care about showing them the sparkly side of European customs and surprising them with the seductions of our luxury.” To that end, the ambassador puffs up the trappings of his own high importance and sets off belatedly from Irkutsk with a retinue of two hundred and forty people, which he considered “necessary for a man of his quality and rank.” They get as far as the Mongolian border when he receives a letter from the king, on behalf of the emperor, who wants him to leave some of his large group behind. He is also asked for the list of presents he is bringing for the emperor, normal protocol. Potocki explains: “China being the most ancient empire in the world, the emperors consider themselves older brothers to all the kings on earth and demand of them not submission, but a certain deference.” As the writer repeatedly shows, the ambassador and his advisors didn’t much bother to do their homework.

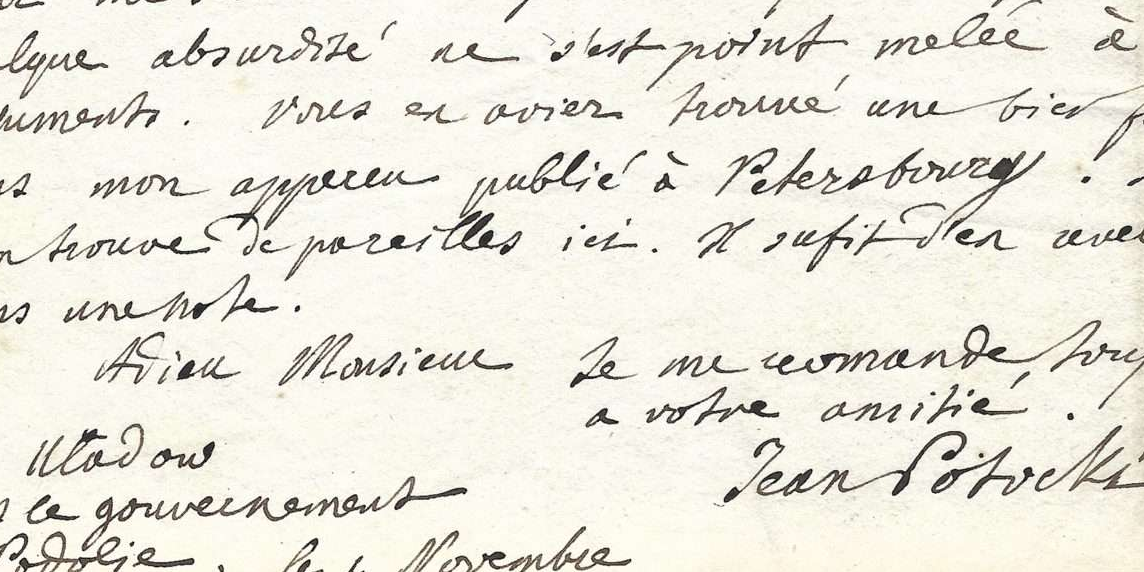

Potocki, a Polish aristocrat with Ukrainian roots, who wrote in French and had produced extensive accounts of his travels through North Africa, the Mediterranean region, and the Caucuses, held a curious position in the delegation: ostensibly an advisor, he ended up more an observer. In 1805, he joined the Asian division of the Russian foreign affairs office, and soon was named head of the scientific section at the new Russian embassy in China, or so went the plan. He was forty-four years old. In the months prior to his departure that summer, he published several historical works and also the first small editions of early chapters from his singular delirium of a novel, Manuscrit trouvé à Saragosse, which would occupy him until the end of his life ten years later. His report on the troubled mission to China, twenty-six book pages long, was intended for government people back in Saint Petersburg, that they should know why it failed. He recounts the autumn months stuck at the border while the ambassador sends letters back and forth negotiating the size of his embassy. When at last a much reduced retinue of seventy people is allowed to enter Mongolia, they are not sufficiently prepared for the severe winter. In the capital, Ulaanbaatar, they are delayed further as the ambassador continues to make a bad impression on the king by refusing to show him the same deference due the emperor, who eventually grows wary and declines their request to come to Beijing.

Ten months in all he was gone, so Potocki must have been more than disappointed to miss out on his chance to visit China. With the ambassador and the first secretary, their uninformed assumptions predictably undermining them, every move was the wrong move. And each time, we might well ask: if Potocki has an understanding of Chinese customs, why doesn’t the ambassador? But further I wonder about the writer himself and the very long voyage he undertook in service to the government (and to his own insatiable curiosity, probably foremost). How long did he think he was going away to China, had the voyage gone as intended? Were his wife and small children going to join him there later? They could hardly be expected to make the journey themselves. And what of his marvelous novel that he was very much in the middle of at the time, did he bring all that with him? (In fact, he did: he wrote a new section of the novel by keeping to his room on the way there.)

The “Mémoire,” we learn, is about an embassy that didn’t exist; that attempted, in its clumsy way, to exist again after eighty years, but it wasn’t going to happen under current leadership. The writer, providing his assessment to government policymakers as part of his role in the delegation, had become a different sort of traveler than he was in his many earlier voyages; more restricted by circumstances, the national entity he was working for. What did exist, as he conveys, was the bitter cold so extreme the mercury froze in the thermometers while they waited in Mongolia in their yurts trying to keep the fires stoked at all hours; and the soot infiltrating everywhere; and the monotony of the daily meal. How had they gotten to such a standstill! As the king tells the first secretary in the end, “I’ll never understand you: we send you to Beijing and you seem to do everything possible to not go there.”

If it weren’t for these buffoons! Potocki must have been muttering some version of that phrase all the way back home. And yet, a cultured man, he would have nonetheless turned the experience to cultural profit. Always he had his books and research with him, even his drawing materials. But he also must have spoken at length with the keepers of the fire in the yurt, and with the king himself, and members of his court, and border officials, the interpreters too of course, and even with the cooks. How could he not ask and talk of all they had to say to him? Maybe none of it was written down, didn’t have to be. He took it with him anyway.