Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera

Medicinal Poetry:

Words, Places, Code-Switching, and Healing in William Carlos Williams’s LanguageTinta regada

1 de octubre de 2024

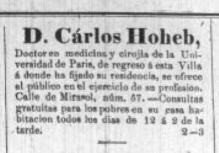

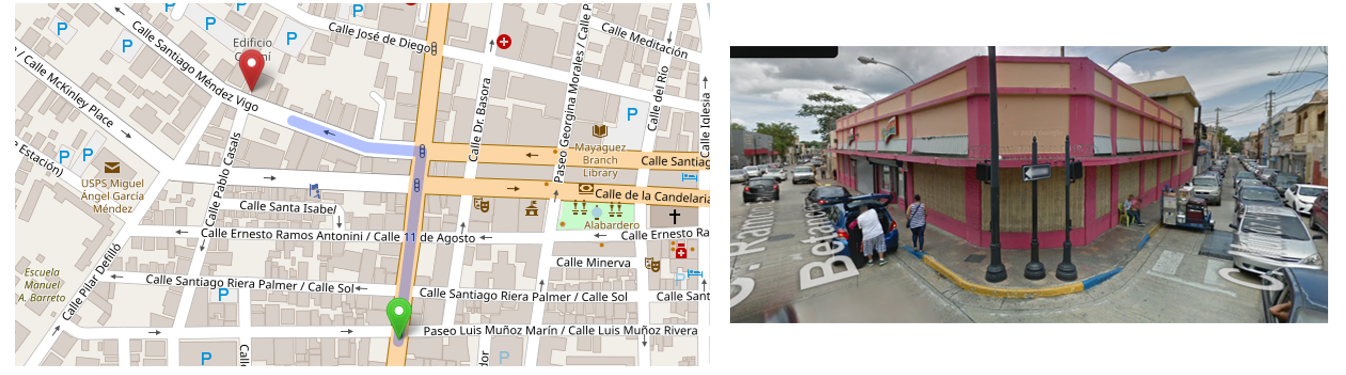

Upon contextual reflection on William Carlos Williams’s connections to Mayagüez, his family links to Judaism, and a period-specific look at the neighborhood where his mother lived on Calle Méndez Vigo, in this paper I would like to argue that the structure of Williams’s poetry was constrained by the medical prescription pads he used to take notes; that his precise use of language joins the physical nature of his profession with his art; and that the depths of his achievement can best—and perhaps only—be understood through his Puerto Rican links, including those to his uncle and namesake, who had a medical clinic at 57 Calle Marisol (Betances/Post).

Este ensayo es translingüe, realizado entre español e inglés y catalán (francés queda oculto), cosa que coordina el argumento con unas sensibilidades metalingüísticas—pero también lingüísticas—de la práctica poética de Williams, y también con su vida. (En otro contexto, quisiera hacer pinceladas hacia vincular a Williams con los autores del Boom, sobre todo en torno de su madre, quien se pondría en un trance en New Jersey para comunicarse con amigos y familiares muertos en el caribe, de otras épocas. Por remate, y la voz de ella en su obra Yes, Mrs. Williams, pudo explorar si no convivir eso.)

In Williams’s life and in his medical practice, Spanish and English evoked specific anxieties, uncertainties, tensions, playfulness, joys and delights, but also tones and methods of perception: in considering both as tools (in medical and poetic practice), this essay pone en marcha una crítica que flexiona e intenta matizar los criterios convencionales, para considerer experiencias más allá de lo que tales límites permiten. Y así, creo, se puede acercar y apreciar mejor lo que él logró tanto como poeta como médico.

“I’m a doctor all day and into the night,” dijo Williams: “I write on the run, or when it’s plenty dark, before going to bed.” He commented on several occasions that he practiced medicine in order to support his writing, and since he self-published his early work, a career in medicine allowed him to explore and develop these talents with the pen. Entonces, who were Williams’s mentors and role models? Who inspired him to follow visions – professional and personal – that lead him to medicine and poetry? What were his links to Puerto Rico, to Mayagüez, and to the Spanish language? What influence does Spanish have on the words he wrote in English? How do those experiences blend into his tone, punctuation, themes, narrative structure and the poetic nuance of his expression? Cómo era el mapa lingüístico de su casa en New Jersey? Y de su oficina? Esas preguntas se acercan temas claves de su herramienta creativa, artística y estética: la palabra. Aunque su madre era mayagüezana, su padre también vivió entre Puerto Rico, la República Domincana y las Islas Vírgenes desde una edad temprana. Lo más probable es que la lengua en que sus padres se enamoraron fuera español. “Mother could talk very little English,” relata William Carlos, “and Pop spoke Spanish better, in fact, than most Spaniards.”

Raquel Hélène Hoheb Hurrad (Elena) was born and raised in Mayagüez – a growing city with several consulates and a lively port. It was a multilingual community, as Marc Pons notes in “Cuando en Puerto Rico se hablaba catalán”:

En 1896 —tan sólo dos años antes del fin del dominio colonial español— Salvador Bermúdez de Castro, director general de Correos y Telégrafos, había prohibido las conversaciones telefónicas en catalán. Tanto en la metrópoli como en las colonias. Pero en Puerto Rico —como los Países Catalanes—, y más concretamente en Barceloneta o en el barrio catalán de Mayagüez (denominado Barcelona), el catalán era la lengua de las casas, de las calles, de las plazas, de las tiendas y de las cubiertas de los barcos. Durante tres generaciones —la de padres, hijos y nietos del siglo XIX puertorriqueño— el catalán fue la lengua con la que aquellos pioneros se amaron, se pelearon e hicieron negocios.

A neighbor of the Hohebs was Pilar Defilló Amiguet, musician and mother of Pau (Pablo) Casals Defilló. Com Pilar era filla d’immigrants catalans a Puerto Rico, la llengua catalana gairebé segurament formava part del rerefons a Mayagüez en aquella època. And, similarly, Elena’s parents were newcomers to the island. Her mother Melin Hurrard was of Basque origin, while her father, Salomón Levi Hoheb, came to the west of Puerto Rico from St. Thomas. Elena was born here in 1847 in a moment when Mayagüez was a hub of Jewish Puerto Rican or crypto Judaic life. This is important to note, as Williams’s grandfather, Salomón Levi Hoheb, like his neighbor Luis Bravo Pardo, perhaps practiced Judaism in secret. As Marta Aponte Alsina and Rossana Duchesne observe, “Her godparents were Manuel Pardo and Cecilia Prieto. They were most probably related to, or the same person mentioned as Mrs. Pardo in whose house Elena’s mother stayed when visiting St. Thomas, indicating that the relations of the Hoheb-Hurards with the father’s birthplace, and his religious community of converted or coerced Sephardic Jews were extended and enduring.”

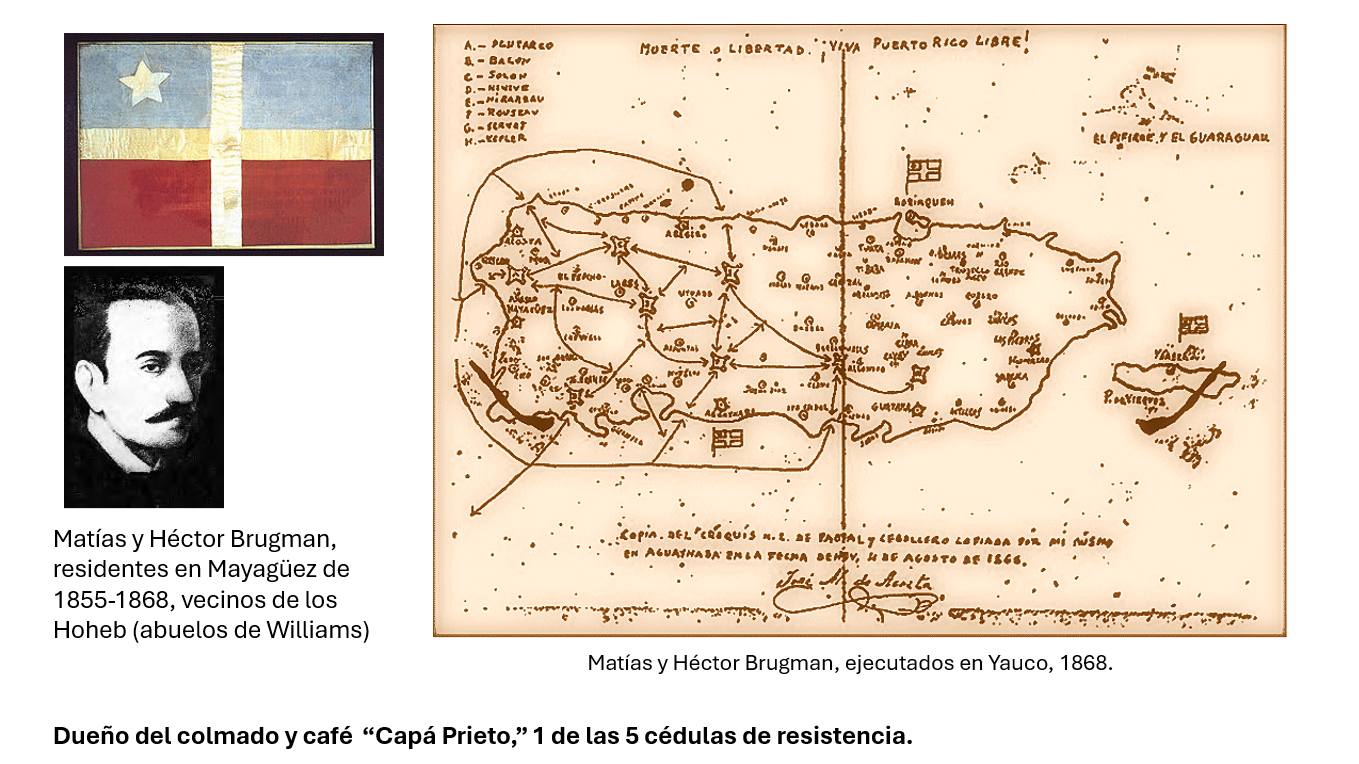

At age 21, Elena experienced one of the key events in the Puerto Rican independence struggle: El Grito de Lares, September 23, 1868, was the largest revolt against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico. One of five resistence cells was in Mayagüez. Among the revolutionaries were several mayagüezanos of Jewish extraction, almost certainly acquaintances if not friends of the Hoheb family. It’s interesting to consider the links between the Hohebs and Luis Bravo Pardo and his family, as well as Mathias Brugman and his son Héctor, all of Jewish extraction. They were neighbors in Mayagüez, sharing holidays and festivals, but also the typical conversations of the day—about politics, Spain, independence and the antisemitic culture in which they lived. “Los judíos,” notes Bravo Vick, “aún los conversos, se seguían sintiendo discriminados por los españoles” (53). He continues that, “la vida en Mayagüez” was a contrast from the San Juan area, with “ricos hacendados, obreros pobres y hasta esclavos, gente muy culta y analfabetas, incondicionales hasta liberales, rebeldes y revolucionarios” (47). And the Jewish element was alive, as the Bravo Pardo family put emphasis on “enseñarle a su hijo sobre la Torah” y “siempre guardaban ‘the Jewish practice’ o ‘the Jewish in me,’ como decía una de las bisnietas de Sarah y Salomón, repitiendo las palabras de su abuelo Luis [Bravo Pardo, vecino de los Hohebs].” One would hear “el ladino o judío español, la lengua judío sefardita” in Mayagüez (61).

The Brugman family had a colmado/dry goods/grocery where part of the Grito Lares rebellion came together. Brugman and his son Héctor took part (Mathías had a central role) and were both executed by the Spanish. This detail is worth of note because, “a military court imposed the death penalty for treason and sedition on all prisoners. Nevertheless, in an effort to ameliorate the tense atmosphere on the island, the incoming governor, José Laureano Sanz, dictated a general amnesty early in 1869 and all prisoners were released.” As occurred with Simón Bolivar in South America, there was an important Sephardic dimension to the Puerto Rican rebellion and, perhaps, in these death sentences as well: the colonial, state-murders in the revolt appear specific to one demography. The Brugmans were among the only rebels to be executed.

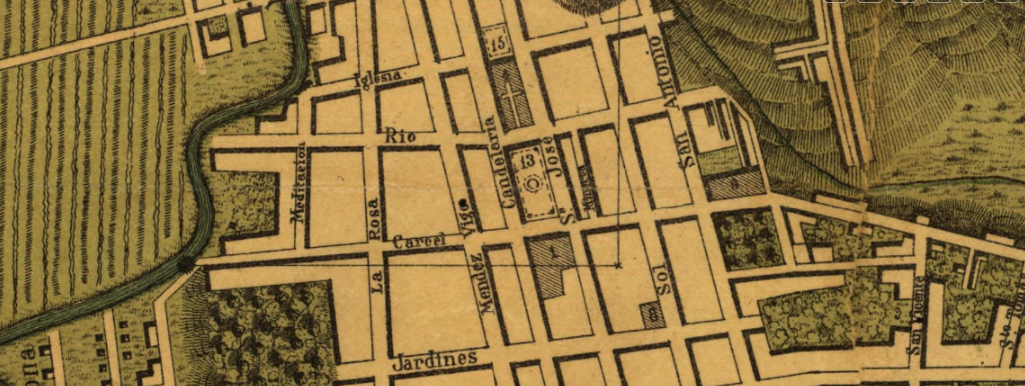

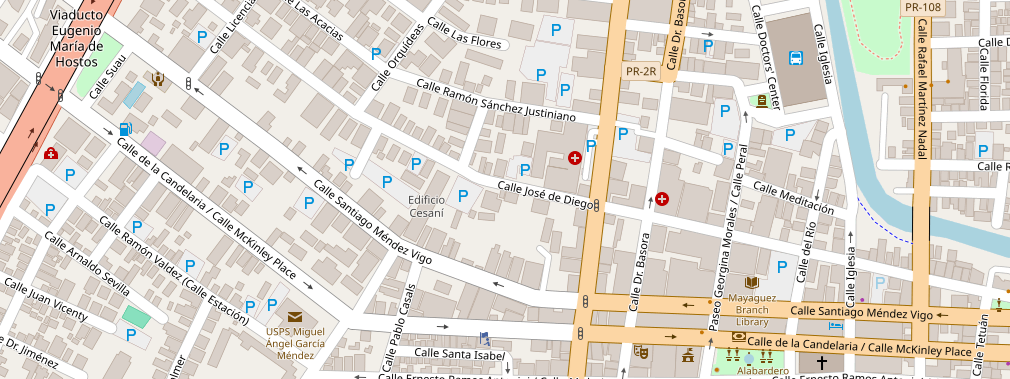

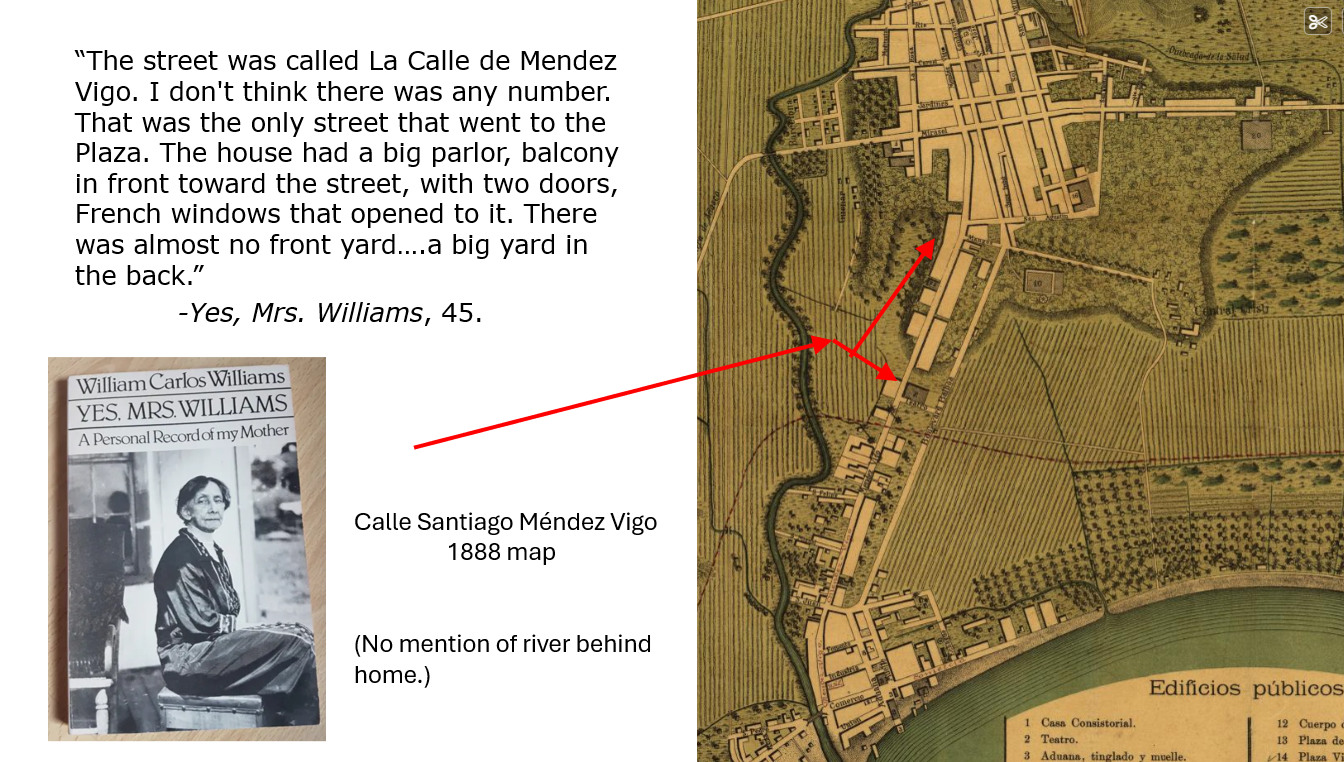

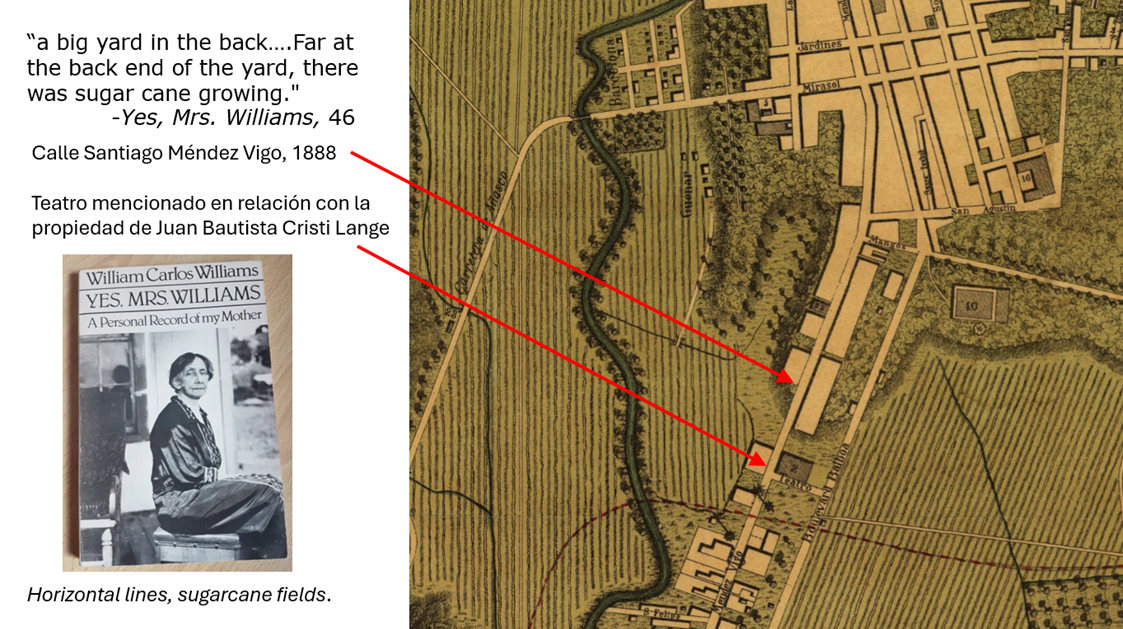

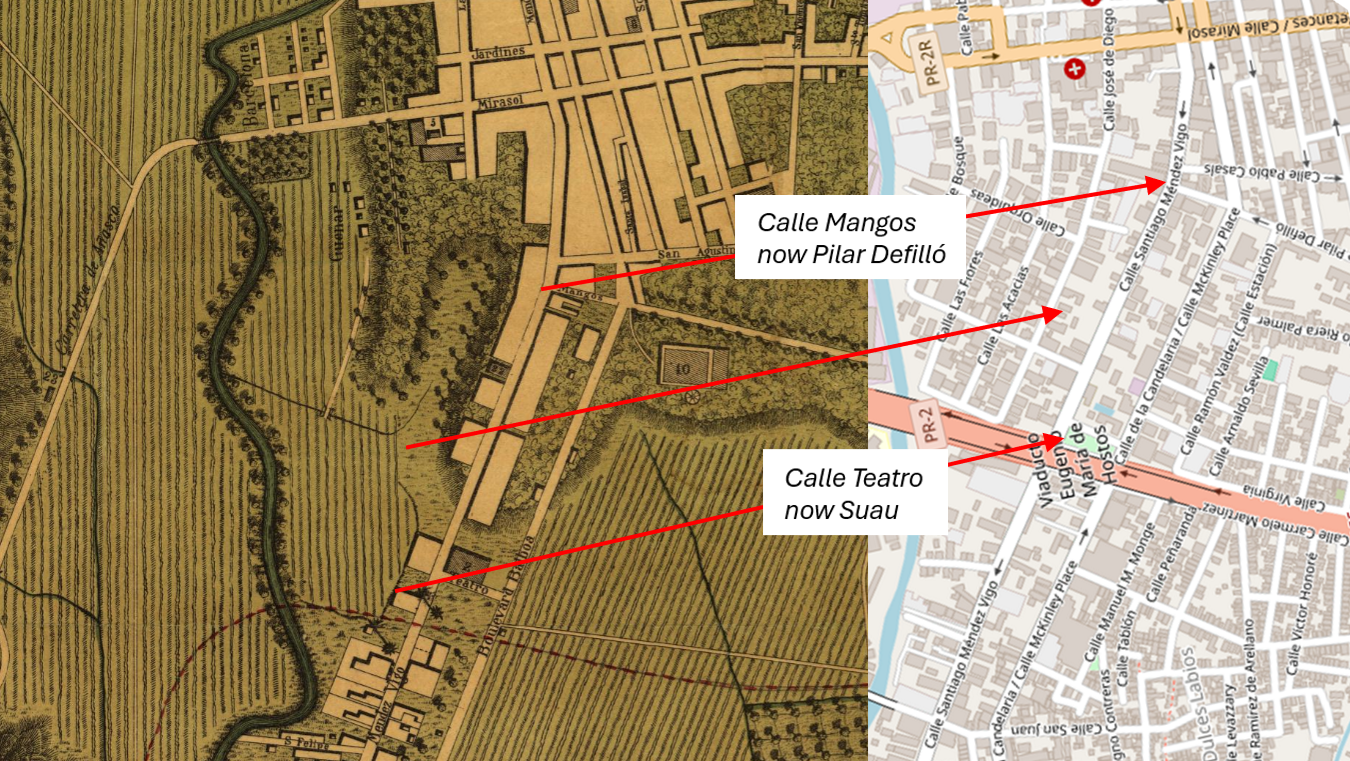

These circumstances place Elena right in the middle—personally, religiously, politically and culturally—of perhaps the most important event in Puerto Rico that century. Partly in relation to that context, an important topic is the precise location of the house where she grew up. This map, from 1888, has the geographic and physical features of the area, while this link is a contemporary view.

In Yes, Mrs. Williams, she recalls:

I’m trying to remember the house. The street was called La Calle de Méndez Vigo. I don’t think there was any number. That was the only street that went to the Plaza. The house had a big parlor, balcony in front toward the street, with two doors, French windows that opened to it. There was almost no front yard. Inside between the windows—I am trying to remember everything I can—there was a big mirror. In front of that, so that the one who played it was with his back to the mirror, was an upright piano, and back of the piano, in the room, was the little organ that my brother played.

….a big yard in the back. There was a big portón that was never opened. You would come up the stair, big steps, at the back to the hall and from there into the parlor. Then along the hall next to my mother’s room there were two or three other rooms. Next to her room was a dressing room and a cabinet.

Last there was a steep pair of stairs…Then going down the stairs, outside, there was a stable with a horse and under the kitchen a place where they had a carriage and the two colored men slept. Far at the back end of the yard, there was sugar cane growing. (45-46)

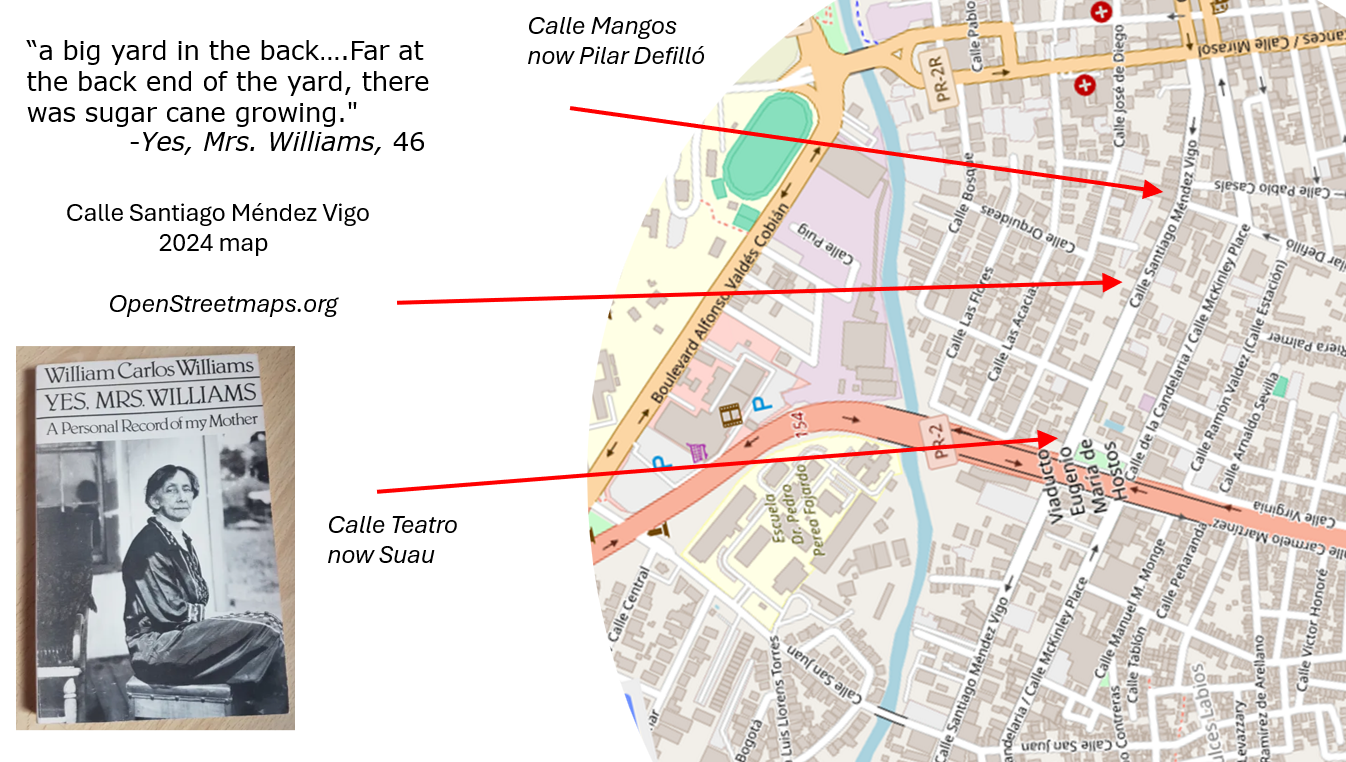

A“big yard in the back” would suggest the home was on the north side of the street (the south side would have another street, rather than a yard, behind). The lack of mention of the river, which is close to Méndez Vigo on the lower sections, would indicate an area closer to the Plaza, between Calle San Agustín (now Calle Casals) and Calle Teatro (now Calle Suau). Marta Aponte Alsina notes that the Hoheb home bordered a large estate owned by Cristi Lange family. That plot was divided after in 1841 as part of the ensanche, and theGaceta de Puerto Rico from 1885 situates the Cristi Lange estate adjacent to where the theater had stood.

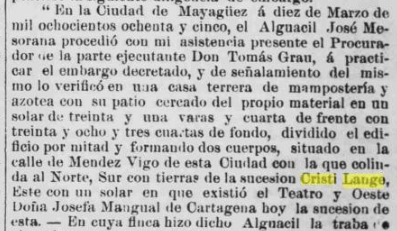

una casa terrera de mampostería y azotea con su patio cercado del propio material en un solar de treinta y varias y cuarta de frente con treinta y ocho y tres cuartas de fondo, situado en la calle de Méndez Vigo de esta Ciudad con la colindada al Norte, Sur con tierras de la sucesión Cristi Lange, Este con un solar en que existió el Teatro y Oeste Dona Josefa Mangual de Cartagena hoy la sucesión a esta. (Gaceta de Puerto Rico, 1885, 8)

In the below images, horizontal and vertical lines indicate sugarcane fields:

In the image above, the lower arrow marks Calle Teatro (now Calle Suau), aside the location of the Cristi Lange estate.

As the home had a “balcony in front toward the street, with two doors” and “French windows…almost no front yard,” the building would have a similar design as the Pilar Defilló Amiguet residence, on the same block between San Agustín and Teatro.

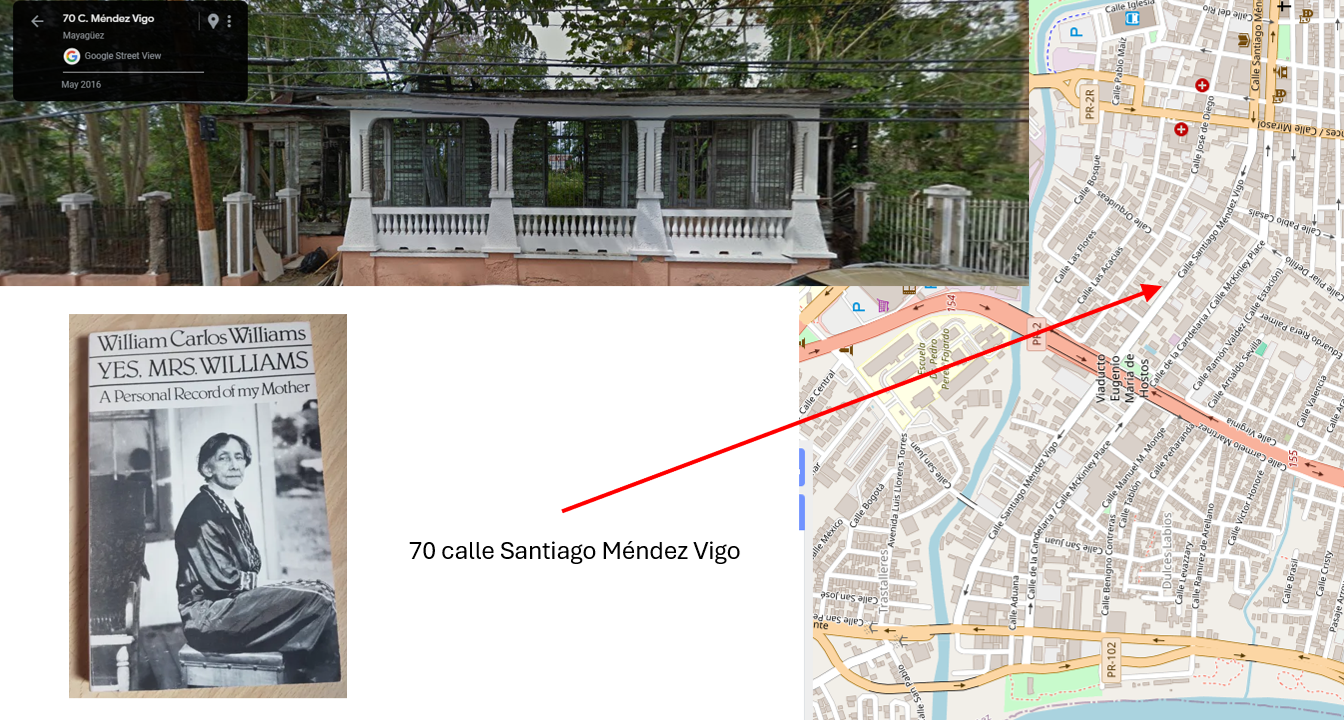

Given these pistas, the location may be on the north side of Méndez Vigo, perhaps one of the two buildings on and just above the middle arrow on the above map, from 1888. Today these locations are numbered 70 and 90. One of the two remaining edifices in the area in the 2010s, number 70 Calle Méndez Vigo, was recently demolished:

Another glimpse of nineteenth-century Mayagüez:

Dr. Cárlos Hoheb

Doctor en medicina y cirugía de la Universidad de París, de regreso a esta Villa [Mayagüez] a donde ha fijado su residencia, se ofrece al público en el ejercicio de su profesión. Calle de Mirasol, núm. 57. — Consultas para los pobres en sus casas todos los días de 12-2 de la tarde. (La Razón, 10 de diciembre de 1871.)

Calle de Mirasol, 57, where William Carlos’s uncle had a medical practice, would be on Post/2R/Betances/Mirasol, around the corner from Méndez Vigo.

As Paul Mariani notes, “As a young girl, Elena had known a modicum of wealth. Her father owned a permanent home in Mayagüez and a summer residence as well. And she remembered her house always being filled with servants [including slaves]” (16). She studied in Paris: “from 1876 until the end of the decade, Elena studied art at the School for Industrial Design [L’Ecole des Artes Industrielles] in Paris, living with her cousins Alice and Ludovic Monsanto in a small ninth-floor apartment in the Rue Notre Dame des Champs” (16). In Yes, Mrs. Williams, he comments that “she was no more than an obscure art student from Puerto Rico, slaving away at her trade which she loved with her whole passionate soul, living it, drinking it down with every breath—the money gone, her mother as well as her father now dead, she was forced to return with her scanty laurels….From Paris she returned to these meager islands” (5).

An important medical but also literary event in William Carlos Williams’s Parisian experience involves another Modernist who would later move to the Caribbean—Ernest Hemingway. As described in Autobiography: “Rode a bus to the Louvre and walked thence, buying a few stamps at the outdoor market on Champs Elysées for Bill…ate at Trianon then to Dôme me. Met Hemingway on the street, a young man with a boil on his seat, just back from a bicycle ride in Spain. The three of us [Bill Bird] back to the hotel…” (212). While in Paris Williams gave medical attention to Hemingway’s first son, Bumby, an event monumentalized in Jack Coulehan’s poem “William Carlos Williams circumcises Ernest Hemingway’s first son.” In a letter from January 14, 1951, he writes: “Do you realize that when I was in Paris in 1924 I retracted Hemingway’s oldest boy’s foreskin for him while the redoubtable lion hunter almost fainted?” This operation occurred at Hemingway’s second Parisian apartment, on Rue Notre Dame des Champs, the same street where Elena had lived in the 1870s.

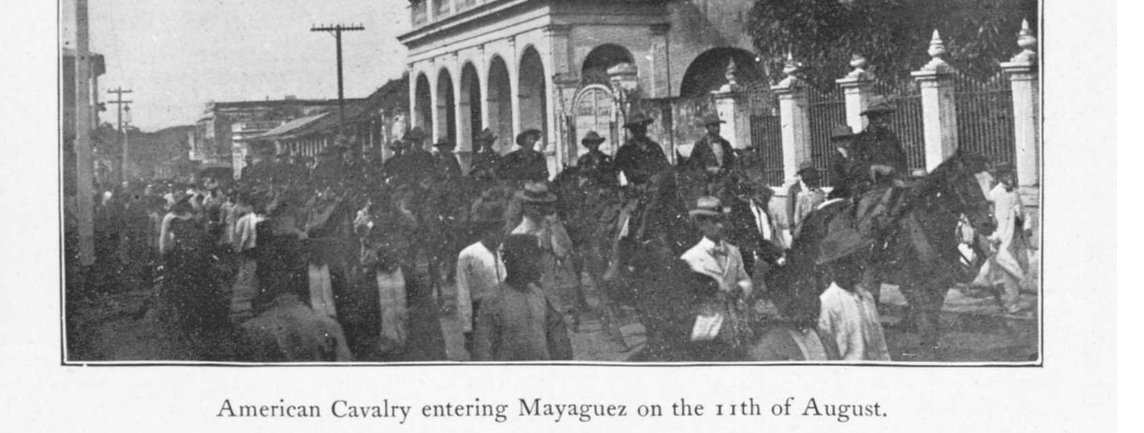

Elena and the Williams family would follow the details of the Spanish-American War from afar. When US troops invaded Mayagüez in August, 1898, they marched up Calle Méndez Vigo:

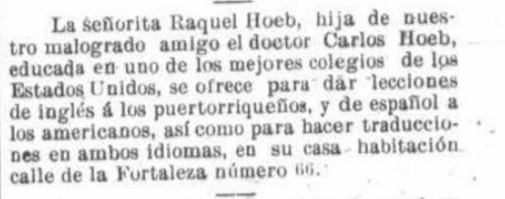

A year later, William Carlos’s cousin, also Raquel, was working as a language teacher and translator in Viejo San Juan:

La señorita Raquel Hoeb, hija de nuestro malogrado amigo el doctor Carlos Hoeb, educada en uno de los mejores colegios de los Estados Unidos, se ofrece para dar lecciones de inglés á los puertorriqueños, y de español a los americanos, así como para hacer tradiciones en ambos idiomas, en su casa habitación calle de la Fortaleza número 66. (El territorio, 6 de julio de 1899, 9)

Williams was born to a home between empires, where languages, religions and cultural traditions would appear and disappear, depending on the context. He blended but also crystalized these experiences, silencing some but voicing others, into a unique form of English. “What Williams heard as a young man,” notes Paul Mariani, was Spanish from his parents but also “Spanish from the lips of the Hazels, the Lambs, the Dodds, and the Forbeses” (17). Williams rarely mentioned in print that he spoke Spanish, nor that it was his first language, though concerning a trip to Mexico, he deflected that part of his experience and that part of himself, saying “My Spanish wasn’t so hot” (Autobiography 73).

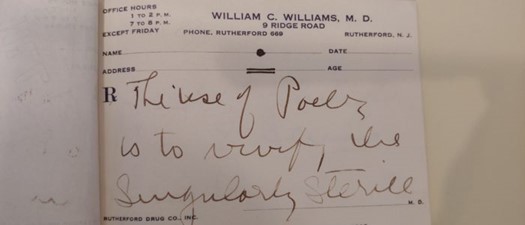

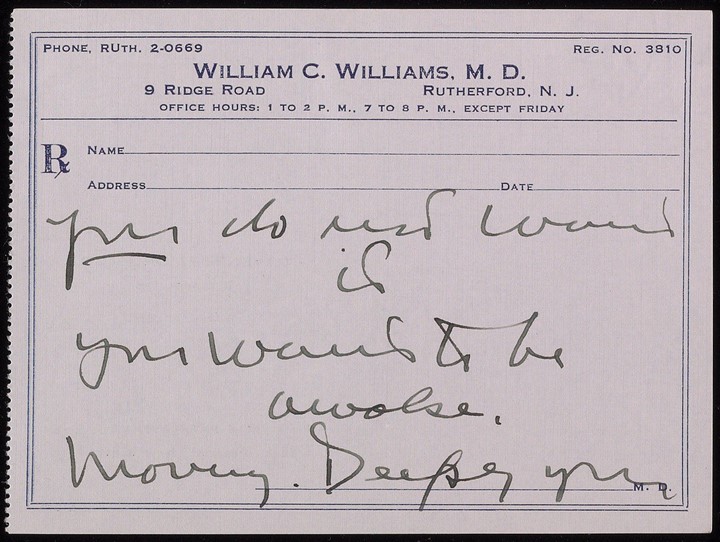

Several languages, places, and literatures scaffold Williams’s poetry, but so do the writing pads he used to record his initial verbal images. (Audrey Ruan has published some delightful reflections concerning these notepads.) Williams said he wrote all the time: between patients, enroute to house calls, in the morning, evening, afternoon, during his lunch breaks and behind the wheel. His pad was always there, and the physical nature of repeating that exercise, of writing in a confined space, became part of his craft.

The pads in question are 5×4 inches, and each has uniform information: Williams’s address, contact information and hours of operation, with a central area of 3.5 x 4.5 to write instructions and prescriptions. The pads bring together Williams’s passions: medicine and poetry.

A precise use of language is important when writing prescriptions, but it is essential to interacting with patients. Physician-patient communication is an exchange of health information, but it is also about relationships. Medical professionals often avoid uncertainty through specific, clear, concise language. Actors often say they stay in character all day while filming, and this mindset likely exists across other professions, including medicine. If doctor-communication has specific tendencies—avoidance of emotions, clarity over verbosity, a close focus on how sound links to meaning—Williams’s prescription pads offer a unique insight into his craft. As he jotted on the notepads, his medical mindset may inform his words, but so do the physical spaces themselves: one cannot Kerouac-esque or Melville an idea along. The dimensions of both the pad and the mindset command pithy, crisp expression that fits the space available.

Audrey Ruan argues that poetry provided Williams a thematic symmetry to the exactness of medical practice. While his profession requires certainty, “Poetry, of course,” she writes, cultivates and even “intentionally seeks … ambiguity.” She continues, “his notes emphasize this aspect of poetry: it is imagination, a ‘force not to be captured’ that will heal people, where medicine falls short.” One can read Williams’s poetic notes as a form of constrained writing; and given the importance of these pads in his imaginative process, the small space in which he inscribes letters and punctuation has important links to his architecture of language—and therefore of healing.

In Williams’s notes we find a commitment to science and imagination. His poetry centralizes experience in ways that escape the limits of medicine, but both fuel one another. Williams commented on this interrelation: “It’s no strain. In fact, the one [medicine] nourishes the other [writing], even if at times I’ve groaned to the contrary.”

“effects of poetry on human vitality.”

“The use of poetry is to vivify,

the singularly sterile.”

Blurring that line—a practical, medicinal use of language blended with the sublime—was perhaps central to Williams’s logic of poetry.

Es importante notar que, a la misma vez, the 1960 census reported 892,513 Puerto Ricans en EEUU, y 70% vivían en el noreste. Williams trabajó como head pediatrician at Passaic General Hospital. El informe sobre “The Puerto Ricans in New Jersey” de 1955 señala que “Puerto Ricans frequently used [Paterson] pre-natal and post-natal clinics.” Williams hubiera atendido con frecuencia a gente de la isla de su madre, hablando y escribiendo en español para ello, con los mismos recetarios a la mano. “The Puerto Rican,” comenta este informe, “is a second class citizen in his community. He is discriminated against in churches, schools, homes, places of public accommodation, and employment.”

Si la poesía intenta concretar lo que existe más allá del alcance de las palabras, creo que Puerto Rico era eso para Williams – una poesía de existencia. Era más allá de lo que conocía y una existencia que quería conocer. La isla y sus tradiciones mantenían el misterio que encarnaba su madre. A través de ella, tuvo ventana a otro mundo, a otra época—y creo que por eso su libro Yes, Mrs. Williams sobresale en su corpus. Y quiero decir que sobresale en tema, pero también en elocuencia y experimentación. Es un espacio para Williams explorar e intervenir sobre esta isla y su cultura, y como tanto, sobre su madre. Su viaje aquí hizo posible que viera lo que su madre vio, que conversara con los vecinos en las mismas calles que ella caminaba. Y ese viaje a Mayagüez de Williams deja mucho que contemplar: con quién conversó. Los edificios que contempló. Los platos que saboreó. Las vistas y las risas que gozó. Las experiencias que buscó.

Pero si dividamos la existencia y la experiencia de Williams, en relación a su profesión, en relación al lenguaje, a lugares, a distancia, a la emoción y a la supuesta naturaleza física que las une todas—es decir su aplicación verbal (si no medicinal) por la poesía—su excursión acá a Puerto Rico hizo posible que contemplara, que viviera y que viera cada uno de estos contextos por experiencia prima. A place where he could be himself in another way.

“¿Cuánto incluyó del silencio?” Una pregunta acertada de Beatriz Llenín Figueroa, durante la conferencia de Marta Aponte Alsina. Indeed, how much silence is in Williams’s English? What does he say in and with that silence? How does it shape his interest in Puerto Rico, his fascination with Mayagüez, and the time he spent in the city? Estas son preguntas que aportan profundidades que se acercan en las novelas de Marta Aponte Alsina, en los textos críticos de Julio Marzán y María del Pilar Blanco, y en las traducciones de Jonathan Cohen. Me conmueven esos textos, tal vez no tanto como la obra Yes, Mrs. Williams, pero me conmueven mucho, porque participan en una tradición que Williams mismo atrevió lanzar: cuestionar distancia, lengua, religión, estado político y selfhood por la obra poética.

Williams, William Carlos. 1959. Yes, Mrs. Williams: A Personal Record of my Mother. McDowell.