Jason Weiss

Polish Journal, 1987 (slide show)

Tinta regada

9 – enero de 2026

We came back to Chabowka from our short detour to the south looking again for the number of a house where a man named Jozef Pedzimas lived. He was the brother of Robert’s paternal grandmother and supposedly he was still alive at 91, though blind. I stayed in the car while Robert asked the woman standing here near a schoolyard. I believe there’s a Pedzimas at the school, she replied, and within moments a shy seven-year old named Tomasz was getting in the car with him. I think we’re cousins, Robert tried to explain to him following the boy’s directions, which for us consisted in knowing the words for there, here, and maybe left and right by then. We pulled up to a modern house, not realizing we were already in Rabka, and a pretty teenage girl, with long dark hair and bright intelligent eyes, met us at the door. In the hallway behind her, a round old woman watched over us. Robert gave the man’s name and the girl said, That’s my dad. But we were looking for an old man. Then she caught on and explained that it was also the name of her grandfather. She reached for her coat and got in the car to lead us to them. We dropped little Tomasz back at school on the way.

*

Up a dirt road we entered a yard where two small dogs barked ferociously at the end of their chains. We hardly saw a large dog anywhere in Poland. Before us stood the farmhouse with the address we had sought, and to left and right were barns. Beyond the further barn, we found Jozef Pedzimas the son, his wife Elzbieta, and a neighbor, who is leaning over the tractor. The girl is Margozata, the jewel of the family who led us there. Robert told her his sister has the same name. Jozef, who is strong and wiry, worked as a miner for ten years in Katowice where he met his wife. She, like their neighbor, is shaped roundly, more common for their age. They are delighted at our arrival, saying they did get the letter but did not understand the return address. Robert asks if old Jozef is inside and they reply that he is. At every turn, Margozata is doing double duty so that we all may communicate, though she speaks no English. And it is a while before I hike back down to the car to salvage our dictionary. They bring us inside, where his aunt insists on feeding us, and later we join her and her daughter to fetch their four cows at the top of the hill, while I ask Robert questions about farm animals that only a city boy could ask.

*

Old Jozef sees what the rest of us move too quickly to follow. He sits by the window and watches the sun climbing over the fields. His farm was burned down twice, once by the Germans. He is speaking here of his sister, whom he never met and who emigrated to America in 1890. I try to calculate how old she must have been, it was a big family. Robert didn’t know his grandmother either. When old Jozef speaks, he gets going for a while, till Margozata tells him that we don’t understand. Then he tugs on the outermost layer of his tattered clothes and jackets. He remembers little of his parents. Robert asks him about other family, those who emigrated, those who stayed. Elzbieta brings out the photo album and Robert recognizes some of the aunts and uncles, others he never met though they live in Chicago. Very few who went away were ever seen again, America was too far. His aunt shows him the letter he sent from Paris, now part of the collection. Robert’s amazement washes over him in waves, to find this living link to the old country, family he never knew existed. He is finding new reflections of himself. Soon his uncle must go back out to work and after we have brought the cows back in, and she has shown us the rest of the barn, his aunt must milk them. Margozata will lead us home.

*

Like most country homes we visit, the entry of the newer house in Rabka is piled with heads of cabbage. We take off our coats in the hallway, after parking the car in the yard by a pile of coal. Margozata’s hands rise into the air in this shot as she takes us into the living room, telling us to make ourselves at home. Her parents will return at night when they have finished working. In the kitchen, we have been introduced to babcza, Elzbieta’s mother, who is shaped like a sack of potatoes and is always smiling or giving advice. Usually, she sits in her chair by the stove, peeling, slicing, preparing the meals, and feeding the fire. Behind the door in the kitchen is her bed. When we are all gathered in the living room, she hobbles in too and takes a chair by the heater, though she never eats with us. Soon, little Tomasz is back from school with his sister Katarzyna, a bit younger than her 17-year old sister. Two older sisters are married with families, they live to the north, we only see photos of them. The two younger children are shy; Margozata shines among them but is loving and kind. She brings us tea and sits to talk with us. We forget that we don’t speak each other’s language.

*

This is our buddy Marian, a distant cousin. Robert later recalled that his great-grandmother’s maiden name, old Jozef’s mother, was the same as Marian’s. It got so I was helping him figure out his own family tree. We have not yet had supper, sitting at the table, when Marian walks through the door here. He has just returned from Czechoslovakia where he works and has brought the children a model racing car set. Four of us cannot manage to assemble the tracks, it does not seem to fit, till finally it works. Tomasz crashed the cars around every curve. Marian returns one weekend nearly every two months, but we never ask him much about life over there. He is in his forties, and his rugged good looks reflect a stubborn inner fire. A bottle of vodka is opened and gradually after several rounds we empty it. This is not difficult between the four men, the mother, and babcza. Marian takes us on as his own special project for the weekend, teaching us Polish whenever he can. He doesn’t give up, talking on into the night with us like we’re old friends.

*

The next morning, we drove an hour south into the Tatras Mountains near the Czech border, to the resort town of Zakopane. This old house is typical of the region, all wood sides sealed with gypsum, with ornate lace-like carvings along the porch railings, the window and door frames, and under the eaves. There were many newer buildings too, including a huge church that surely would not be finished by winter. Already it was almost cold enough to snow and each morning frost covered the land. Robert especially liked the scaffolding we saw everywhere in Poland: wood mostly, lots of two by fours, nailed and tied and splinted together, like a futurist stairway to the sky, it didn’t look like it should hold. Witkacy, or Witkiewicz, lived a while in Zakopane, we saw a theater bearing his name. Interesting how the avant-garde of yesterday becomes the pride of today. Marian came with us, we were only there a few hours. We walked up past the shops and onto the road that led into the mountains. Robert wanted to really hike up there, away from the town, but there wasn’t enough time. The whole trip was like that in a way, it was bewildering, doors opening in every direction and hardly the time to see where they lead. Instead, we came upon a museum, spending much longer than we had intended inside, where Marian explained to us any way he could geological charts and topographical maps, and we viewed stuffed specimens of the bears, foxes, eagles, and many other creatures, as well as the plant life, of the places we would not reach in person.

*

This black statue, at a corner on our way up the hill in Zakopane, is dedicated to a doctor from the turn of the century whose name I didn’t catch. I believe he founded one of the sanatoriums there. More to our interest was the figure beneath him, who is supposed to be a typical mountain man, or goral, of the time. He’s holding a traditional three-string fiddle which Marian said, I think, is played with the bow strung loosely so that the stick is under the instrument while the hair of the bow is arched over the strings. In this way it is not a melody that’s produced but chords. The fellow’s long hair and floppy hat make him a real Polish hillbilly, or perhaps he represents a late-model troubadour.

*

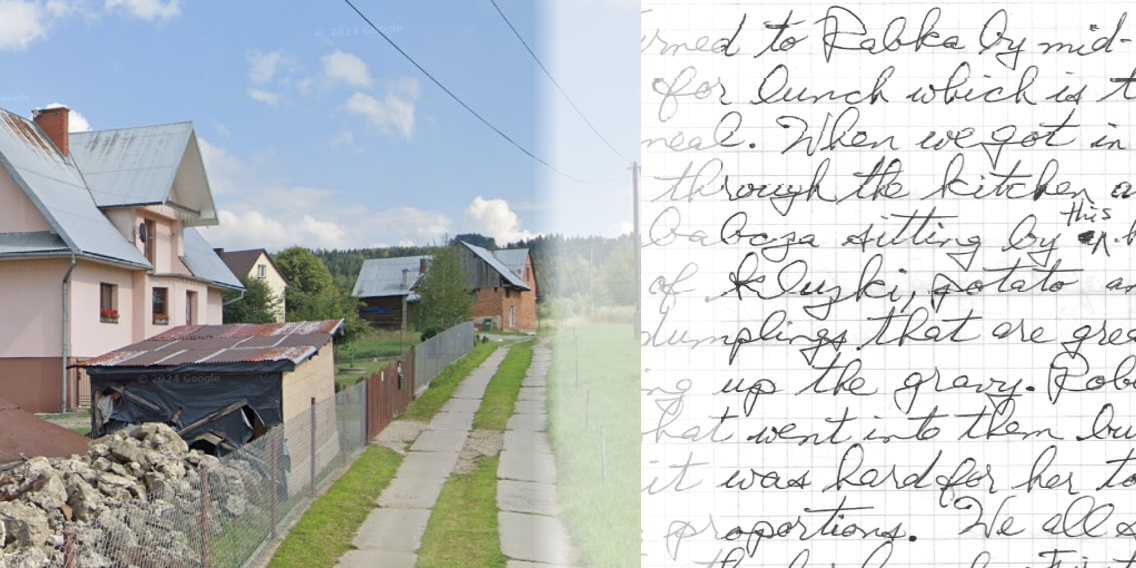

We returned to Rabka by mid-afternoon, in time for lunch, which is the main meal. When we got in, we passed through the kitchen and found babcza sitting by this huge bowl of kluzki, potato and flour dumplings that are great for mopping up the gravy. Robert asked what went into them, but of course it was hard for her to specify proportions. We all sat down together for lunch. First, there was soup, and then the kluzki was brought on, shaped like billiard balls. Once we had been served, Elzbieta carried in the meat, it looked like brisket, and we each were helped to a generous slab of it. We had heard about meat rationing, so we didn’t understand how in this house and elsewhere there seemed to be meat at every meal. They didn’t know when we were coming. Could they have gone through their entire ration for us? Probably in the country, I thought, the shortages were felt less. The pickled cabbage, served as a garnish, we’d seen the day before. Robert doesn’t eat a lot but his aunt wouldn’t have it, she gave him more kluzki. No one had to force my hand. However, it is in their nature to expand once you have eaten them. Still, after digesting, the others scattered to their tasks—the aunt and uncle back to work on the farm, Margozata to prepare flowers for All Saints’ Day the day after, and Marian to visit a friend. We could hardly move, let alone think or read our books.

*

If you think that is a TV in the corner by the model racetrack, you are not mistaken. Those are two characters at a train station speaking in very British English about catching a train next weekend at five. Though I know it’s only an English class on Polish TV, it sounds like it’s from another planet. Almost as inane as my Berlitz book. Robert was already impressed by the programming when on our first night in Rabka Carmen was playing on TV. Later this night, there is an English film that everyone watches. The method of dubbing is the most economical: the soundtrack is turned down a bit and a single voice recounts in Polish every character’s lines. On All Saints’ Day, there is a show about the Russian actor and singer Vissotsky, with reminiscences by famous Polish directors.When Marian got home that night, he was in raptures. Here he is rolling his eyes to heaven while opening the bottle of vodka that we’d bought in Zakopane for the house. Mein lieben, he keeps saying, for he is in love. When Marian tries to explain something to us he often slips into German, which we don’t speak either. But given its closer proximity to English, and my minuscule knowledge of Yiddish, I can usually figure it out. On first meeting, he’d asked us if we spoke Russian, as Marek before and others had done, and I could only respond Yah nie panimayu, I don’t understand, which got a laugh at least. But Marian’s love, she is a distant cousin who lives several kilometers away. He is filled with her and can speak of nothing else at first. Soon, though, once the three of us start drinking, the Polish lessons begin. Singular and plural, this is a spoon, these are three chairs, there are five pockets. Robert agonizes over a language that by rights he might have been born with. It is getting late. Marian knows he will not see us for a long time; we are leaving the next day, but we are his friends. He asks Robert when he will return to Poland. Robert doesn’t know and asks when Marian will visit Paris. But Marian is not allowed to leave. He tells us why he must work in Czechoslovakia. He was a lawyer, he started working with Solidarity, and when martial law came down he was thrown in prison for seven months. Perhaps he escaped, we can’t understand exactly though he tries repeatedly to explain, something about bribing the dog with food and throwing hot soup in the guard’s face. As punishment, he has to work abroad there for three years, and can only return to stay in 1989. He is thinking of his love. Babcza calls out from the kitchen for him to shut up, it’s after three a.m. He asks us to write him, in Polish. We say that we will.

Jason Weiss, ganador del premio Ecos en tinta 2025, es autor, crítico, traductor, editor y profesor. Asistió U.C. Berkeley en los años 70, pasó la década de los 80 en París y ha vivido en Brooklyn desde los 90. Tiene un doctorado en Literatura Comparada de New York University. Su páginaweb es Itineraries of a Hummingbird.